Archives

| F | S | S | M | T | W | T |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 |

| 30 | 31 | |||||

Far East and Beyond

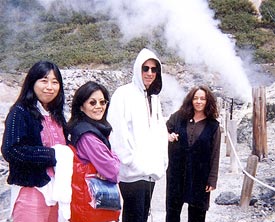

In November, my schedule took me first to Japan. It was a quick stop that included two beautiful celebrations in Nagoya (This Is It!) and Tokyo (Osho Japan). I proceeded on to Taiwan, where I spent three wonder-filled weeks. I knew I was in for something special when I arrived at the airport. There were orchids everywhere! After all, it is sometimes still referred to by its old name, Formosa: the Garden Isle.

In November, my schedule took me first to Japan. It was a quick stop that included two beautiful celebrations in Nagoya (This Is It!) and Tokyo (Osho Japan). I proceeded on to Taiwan, where I spent three wonder-filled weeks. I knew I was in for something special when I arrived at the airport. There were orchids everywhere! After all, it is sometimes still referred to by its old name, Formosa: the Garden Isle.

Taiwan sits on an active faultline, so there are often earth tremors. The larger ones can be quite devastating. Full-on earthquakes. One night I was awakened in bed by a pretty sizeable one, 6.1 on the Richter scale: large enough to make the buildings sway in Taipei. My sannyasin friends laugh it off: “It is just the earth dancing, being happy you are here” they’d say. The next morning, an aftershock came during the ‘Hoo’ stage of Dynamic. Everyone re-doubled their efforts and jumped like crazy – including me!

I wish I had some photos to share with you from the Taiwan trip, but I have simply been too busy to gather them from my organizers. Perhaps at some point I’ll have a few to post on these pages, because it was definitely a memorable and beautiful visit. I am sure I will return someday.

After Taiwan, I passed back through the USA briefly and enjoyed Thanksgiving holidays with my family. On December 3, I flew to India. It was my first visit in four years and what a joy it was to be back. My god, that first chai tasted so good. There is something about India that is just indescribable. After all the organization and togetherness of the West, I found the chaos – even the pollution – refreshing. Something deeply relaxes in me when I am there. India is a kind of nourishment for the soul, and mine was thirsty.

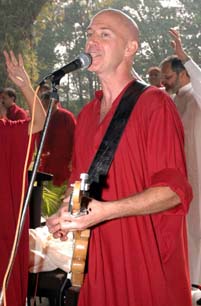

The first two weeks were spent at Oshodham: a beautiful meditation facility southwest of New Delhi where a five-day meditation camp with live-music had been organized. It culminated in a celebration of Osho’s Birthday on December 11. The following day, December 12, the band(Palash and Vatayan) and I played for a gala wedding event – a big shift in gears, but a smooth one nevertheless. And what a party it was. Kya bhat hai!

The following week, I traveled to Dehradoon with Vatayan and Palash and enjoyed more adventures. For example, I hadn’t been on an Indian bus in a long time – almost thirty years! Nowadays, you can ride in air-conditioned comfort and sing-a-long to soundtracks from the Hindi movies that run continuously. My memories from earlier times are of sitting next to turbanned farmers and their animals for hours on end, and eating tons of dust as the bus bumped along, somehow managing to hit every pothole in front of it. Our overnight stay in Mussourie, a picturesque hill station high-above Dehradoon, was a highlight. Sitting on the balcony of our hotel room, sipping chai and munching pakoras, I watched the sun set over the main range of The Himalyayas. The next morning, the haze had totally cleared and the view of the mountains was uninterrupted in all directions. Unforgettable.

Next, I traveled south. I hadn’t been to Goa in twenty-six years. Although the quiet coconut grove that is now Candolim has been developed, it is still possible to savor the relaxed and easy atmosphere unique to this part of India. I had Christmas dinner at Demelo’s, a popular sannyasin gathering point where I dined on the beach under the stars, a world away from the powerful waves that were devastating the eastern coast of India and Sri Lanka. Walking along the beach that evening, a strange surge from the sea brought the water up around my ankles twice. I stood and waited, alert. I guess that is how it happens: from out of nowhere the waves come, so suddenly and without warning. The next day, I heard news about the devastation and called home to let my family and friends know I was OK.

After enjoying a few more happy days with friends in south Goa, we took the Goa Express to Pune, arriving just in time for the New Year’s Eve celebration at The Resort. It was so wonderful to see many familiar faces again as I danced out of the old and welcomed in the new. The next day, I played for sannyas celebration in the new pyramid Auditorium: a perfect way to start the New Year. I found the improvements within The Resort to be first-class. And the masala dosas are still good at The Madhuban!

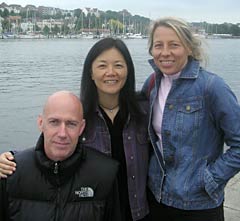

A few days ago, passing through Stockholm on my way to the States, I met a friend for coffee, and we marveled at how strange time and space are: One minute you can be talking with each other on a busy street corner in Koregaon Park; then suddenly you are gossiping together in a cozy coffeeshop in Sweden. The world has become a small village in many ways. And we are most certainly its global citizens.

|

|

|

|

|

I had just finished giving a concert in a small Japanese city called Shizuoka. Some friends invited me to stay in their house for the night. They lived outside the city in a large, traditional-style Japanese farmhouse made of wood with paper walls. In one part of the house, their grandmother had been living with them. She had died one day before. The musicians I was traveling with were each given a choice which part of the house they would like to stay. Our host turned and offered me Oba-chan’s room (oba-chan is the Japanese word for grandmother) saying she said she thought I would have more space to rest there as long as I felt comfortable with the situation. So I graciously accepted her offer. Stepping through the door to Oba-chan’s room, I couldn’t help noticing the official certificate of death tacked over its entrance, having been placed there by the local Shinto priest. I assured my hosts I would be fine and we all said goodnight.

Alone in the room, I could sense the presence of death still hanging in the air. It was tangible, like a vibrating stillness I felt I was on sacred ground and bowed to the shrine in the corner. Lighting some incense sticks, I placed them carefully next to the buddha statue in the shrine. A small mirror had been placed at the shrine’s center.It is one of the Zen influences of Shintoism has absorbed, the significance being: whoever seeks God by looking in the shrine will see their own face in the mirror.

I lay awake a long time that night before finally drifting off into a deep, dreamless sleep. The next morning, I awoke feeling refreshed, and grateful to Oba-chan for the opportunity to have participated in the mystic experience of her death. Taking up a pen and paper, I wrote down the following poem in her honor and to say thank you.

In the corner of my small house

An altar with a mirror shines

Empty and clear

Reflecting ripples on the lake

My shoes wait now

Patiently by the door of

This house where I lived a life

Where only moments before

I laughed in the sun alive in this

Mischief

Kind people come today

They sing and play their instruments

As is their joy

Their laughter carried by the morning breeze

Echoes through my empty rooms

Someone lights to burn

Fragrant sticks in the room

Where only yesterday I laid

Sick and dying.

Nothing much has changed, only

This is not my house

Anymore

The incense burns slowly

And with each passing day

Soon the memory of me will fade away

Until the mirror at the altar shines

Empty and clear again

Reflecting ripples on the lake

Colors of Celebration

After the Europe tour finished, I rested for a few weeks in the countryside northeast of Stockholm, just a fifteen minute drive to the archepelago. Autumn was already appearing in the form of cool days and nights, while the forests were full of wild mushrooms and blueberries. One highlight of these few weeks between events was my first drive on a Harley-Davidson!

The Varazzee Festival in nearby Genoa, Italy, was again wildly successful thanks to the love and care of its organizers: Nirodh and Ushma. Bellisimo!

Three events made for a short USA tour this year – New York, Cleveland, and Sedona – but the energy in each place was more beautiful than ever. Directly afterwards, I flew to The Bahamas, where I joined friends at Wildquest for a week swimming with the dolphins.

Three events made for a short USA tour this year – New York, Cleveland, and Sedona – but the energy in each place was more beautiful than ever. Directly afterwards, I flew to The Bahamas, where I joined friends at Wildquest for a week swimming with the dolphins.

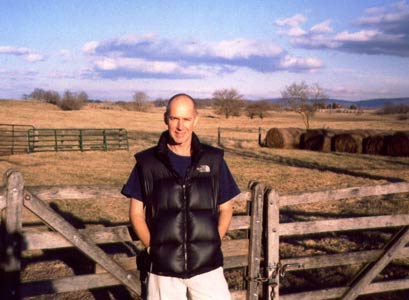

Now another shift in gears and climates. I’m writing this update in Virginia where autumn has definitely arrived. The air is crisp and cool, and the Fall colors spectacular. In just a few more days, I will be on a plane to Japan and Taiwan, where more adventures await – and the next phase of the touring!

There are many pictures to share this time: some from earlier in the summer on the Europe tour, but also some recent ones from the Wildquest trip.

So enjoy – and perhaps meet you along the way!

Osho RISK Summer Festival, Denmark

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Soleluna Festival & Amarti Celebration, Italy

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

USA Tour – New York, Cleveland, and Sedona

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Summer Celebrations in Europe

Since returning from Japan in late May, it has been a busy summer here in Europe. Two wonderful events happened in the far north in June – one in Helsinki, Finland; the other at Angsbakka in Sweden. Then followed the annual Europe tour, which started far to the south in Italy and continued throughout the rest of Europe into mid-August.

Since returning from Japan in late May, it has been a busy summer here in Europe. Two wonderful events happened in the far north in June – one in Helsinki, Finland; the other at Angsbakka in Sweden. Then followed the annual Europe tour, which started far to the south in Italy and continued throughout the rest of Europe into mid-August.

Although summer never quite appeared north of the Alps, the music, meditations and celebration kept us warm and sunny on the inside. There are lots of pictures from this year – over two thousand! It is an understatement to say it is the best documented tour ever thanks to Rishi, our very own paparazzi. It will take me some time to sort through all the photos, and as many of them look good at first glance, I will look for an efficient way to post them as future updates for all to enjoy.

Meanwhile, I am relaxing in Sweden between events – picking wild blueberries in the forest and enjoying the first tinge of autumn in the air. The Varazzee Festival and USA events are on the horizon, so stay tuned and perhaps meet you somewhere on way.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Finland first came under my radar twelve years ago when friend and fellow musician, Sidhamo, moved to the small city of Kokkola with his Finnish girlfriend. They have since married and have a lovely daughter, Iris. At that time to my American ears Kokkola sounded very much like Coca Cola. Perhaps it was my way of coming to terms with a new part of the world I was only just beginning to understand.

A few years later, I saw a photo of Sidhamo on one of his cd: him standing on a frozen lake surrounded by an endless landscape of ice. It reminded me of a remark another friend once made concerning Sidhamo’s fate: “Now he’s really

fin(n)ished!” Honestly, I wondered if I would ever see him again much less visit there. But alas, existence has its mysterious ways.

I met Pravasi, my girlfriend, two years ago. When I learned she was from Finland, the first thing I did was go out and get a map. Now two of my most-loved friends were connected to a part of the world I had almost no knowledge of. I had to do something!

As life would have it, on June 4 of this year Pravasi and I boarded the luxury liner, Silja Symphony, in Stockholm bound for Finland. The weather was splendid, clear and sunny in the late afternoon, as our ship slowly wove its way out among the thousands of islands comprising the Swedish archipelago.

The cruise was stunningly beautiful. Arriving the following morning to Helsinki, we made our way to the Unio Mystica Bookstore and met its owner, Manik. He also helps coordinate the nearby Tao-Tupa, also known as the Osho Leela Meditation Center: an informal space where people meet for meditation and special events such as mine later that evening.

Manik and I were chatting away when suddenly I heard Pravasi’s infectious laugh coming from outside. And there he was, Sidhamo, my long-lost friend, smiling through the window with little Iris in hand. It was a poignant moment, another of life’s many circles coming round, intersecting, manifesting like a Zen brushstroke. I smiled. I had made it to Finland at last.

We decided to go for cappuccino and along the way laughed as only close friends can — talking about life, love, and nothing much at all. When it was time for Pravasi and me to leave for the event, we all made plans to meet again the next day before our boat departed.

Later that afternoon at Tao-Tupa, my event began with Osho Kundalini followed by Heart Dance and a break for tea. Afterwards, I sang some celebration songs and we all enjoyed to our hearts’ content. I don’t remember the sun ever really setting that night. At least it never got fully dark. Such is the special ambience this time of year in these far-northern latitudes.

My travels are a great teacher and this trip was no exception. My visit confirmed what I have experienced time and again on the tours: The world is a vast and infinitely fascinating place, full of amazing people in all its nooks and corners. Making new friends along the way, such as the lovely Pura and Idar, who cared for our accommodation in Helsinki, or meeting old ones again like Sidhamo — it is one of the things that makes my work so rewarding, nourishing, and keeps it fresh. For example, eeting Manik and hearing his stories — how he started-up Unio Mystica twenty years ago at first selling only Osho’s books and to this day continues to publish Osho’s titles — provided me unique insight into Finland’s connection with Osho.

The next morning, Pravasi and I shopped for a few Finnish food delights at a local supermarket. Then we met Sidhamo and Iris one last time before boarding our boat back to Sweden. As we waved good-bye and sailed off, the fullness in my heart reminded me of a song from the previous night:

This life our celebration

Of the joy we’ve come to know

My love for you, Osho

Is overflowing

Perhaps the sun never sets anywhere in the world for lovers and meditators. At least not in Finland!

Kindred Spirits

It has been a busy time: traveling, on the road in Europe and Japan, enjoying events, the music, good vibes, meditating and celebrating with kindred spirits all along the way.

“The Festival East” in Riccione, Italy was a success this year: an expansion of energy from previous years and supported by the aesthetic, new venue. Congratulations to Videha and Team.

Japan was full of mystery and many surprises as always. I enjoyed the advent of Spring everywhere, which in Japan means many flowers, endless shades of green, and the sweet songs of birds; not to mention the remarkable choruses of frogs in newly-planted rice fields.

More highlights from my month in Japan included introduction of the new Chakraman Meditation. Also my first visit to Okinawa, where I met and played with Upanishad and his wonderful band, Champloose. I enjoyed rainbow-viewing on ‘God’s Island’ – one of the many spiritual islands off the coast of Okinawa. And stayed current with the gossip while enjoying many a good ‘breakfast-set’ with my friend and fellow musician, Pragyana, bass player of the juicy Banana Band from Tokyo.

At the end of my stay, I took time-out to polish my karaoke skills with friends, Mukti and Vimal. I even enrolled in a cooking class and learned to make soba noodles. After a dubious start, I was awarded a compliment by my teacher, who declared my noodles to be: “Good cut, neh?” I thought they tasted pretty good, too! Pictures from this fun-filled time will follow in next month’s update.

End of May finds me again in Stockholm, Sweden enjoying the long days and short nights Scandanavia is famous for this time of year; also preparing details for the upcoming Europe tour. In the current world climate, I can’t imagine a better time to meditate and celebrate, with people who share a positive vision of life: one of love and creativity, not misery and destruction.

‘The Festival East’, Riccione, Italy |

|

Higher Mathematics

There is a branch of mathematics devoted to proving the mysteries of Existence with formulas and equations. It’s a rarefied realm inhabited by a special breed of people: people like Albert Einstein. His elucidation of the Law of Relativity is a good example of what scholars call abstract, or ‘higher’ mathematics. The discoveries in this field can sometimes have profound effects on the world in which we live. Witness the innocent looking little equation of Einstein’s, E=mc2, how when applied to the science of physics helped harness the power of the small atom.

There is a branch of mathematics devoted to proving the mysteries of Existence with formulas and equations. It’s a rarefied realm inhabited by a special breed of people: people like Albert Einstein. His elucidation of the Law of Relativity is a good example of what scholars call abstract, or ‘higher’ mathematics. The discoveries in this field can sometimes have profound effects on the world in which we live. Witness the innocent looking little equation of Einstein’s, E=mc2, how when applied to the science of physics helped harness the power of the small atom.

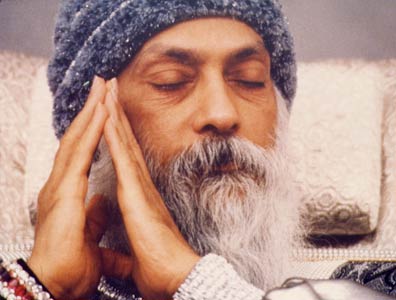

This month marks my 28th sannyas birthday. It was twenty-eight years ago, one cool morning in India, I showed up at the ashram gates for my first Dynamic Meditation. So taken was I by the lucid eyes of the long-bearded sannyasin explaining the stages to me, I spaced-out the directions and breathed like a freight train through the second stage – twenty minutes! I will never forget how psychedelic the world looked after making that “mistake”; nor how alive I felt for the first time in my life. This was my first encounter with higher mathematics – of an inner kind that is.

You might laugh and wonder what meditation has to do with mathematics, but they are quite similar in a sense. For just as there is a science of the outer world, there is a science, or in this case, mathematics of the inner world. One particular formula I have discovered during in these twenty-eight years looks like this: music + meditation + celebration = personal transformation. But as any good mathematician will tell you, formulas need proving before they are can be accepted. So what about the proof for meditation then? Well, there’s a little saying that goes: The proof is in the pudding. Meaning: If you want to know how good the pudding is, you have to taste it for yourself. In other words, let’s do the math. See you at the events this year!

|

|

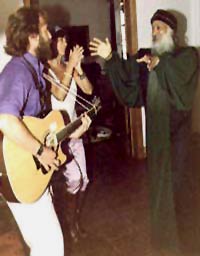

| First dance at two years old with my beloved Raggedy Ann | Dancing with my beloved Master – Osho’s World Tour, Portugal, 1986 |

“It seems that as man becomes more and more intelligent, his crimes also become more and more intelligent. His criminal mind is far ahead of his effort to become enlightened.” Osho, The New Dawn, Chapter 32

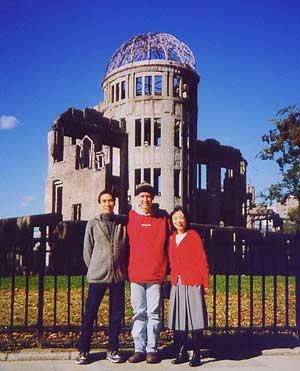

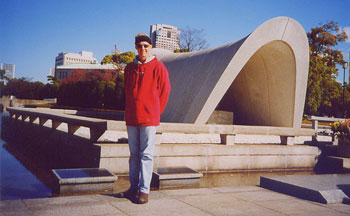

I stood in front of the Atomic Dome at Hiroshima and the tears came from nowhere. I noticed Bhuti, my Japanese friend next to me, was also crying. It was the strong contrast to the wonderful meditation event we’d had the previous day and our lively dinner afterwards with the participants. Standing at Ground Zero seeing for myself the enormous destructive power humanity is capable of unleashing on itself was to say the very least — a deeply moving experience.

The Atomic Dome is one of the few buildings to remain standing more or less intact in the wake of the biggest weapon of mass destruction ever used by one country against another. Motionless, I stood in front of the memorial plaque and read the account of what happened in 1945: How, as both Japanese and American politicians split hairs over how to word Japan’s surrender terms, America went ahead and decided to drop two atomic weapons on the cities of Nagasaki and Hiroshima. It was a decision that effectively erased a quarter of a million human lives in a single moment and one that will forever remain a black spot on the history of mankind.

“America’s whole approach is: everything should be made better They are obsessed with the idea of bettering things. You have to have more speed, better machines, better technology, better railroads, better roads — better everything! And you can see what happened in Hiroshima and Nagasaki: America really did it better than anybody else has ever done it.” Osho, Theologica Mystica, Volume 2

Even among the scientists who helped create the bomb there was opposition, voices of dissent, and caution in the ranks. Japan had already been defeated. It just hadn’t formally surrendered. In the months leading up to the Hiroshima, politicians on both sides of the war fretted over petty details of surrender terms, while at the same time a strong momentum builbing to use the weapon: either as a means to exact vengeance and punish the Japanese for the emotional pain inflicted by the war; or simply to try out Oppenheimer’s new toy, a creation he himself dubbed his “Little Boy”. Whatever the motives, choices were made and the rest — including the innocent people used as a test group — is history.

“And because the whole American system depends on doing it better, then of course, in the same way you need a better man. It is the same logic. Then he fits with the whole American style of life. But the New Man is not necessarily the better man. He will be livelier, he will be more joyous, he will be more alert – but who knows whether he will be better or not? As far as politicians are concerned he will not be better, because he will not be a better soldier. He will not be ready to be a soldier at all.”

Osho, Theologica Mystica, Volume 2

An atomic bomb is no simple thing to make. It takes a certain intelligence to understand its physics, design, and to build it. My point is: Whether you are an uneducated Palestinian mother who blows herself up at an Israeli check-point or a master of atomic physics like Oppenheimer — both individuals are essentially human beings with the same heart beating in their chest. Acting out of desperation or calculation, it is still individuals who make such decisions to achieve certains ends — responsible or irresponsible as they may be. So while I am not in total agreement The National Rifle Association, they do make a valid point: Guns don’t kill people. People kill people. Guns are intrinsically neutral. Just as a bomb is. They don’t go off unless someone pulls the trigger or presses the button. In my opinion, this ability to choose is what defines us as human beings.

“The New Man will have a totally different vision of life. He will not be competitive. He will know that money cannot buy love or joy, that it is not the goal of life. He will live in a more loving way, because to him: Love is richness.”

Osho, Theologica Mystica, Volume 2

What about the issue of responsibility? If we as people have two choices before us, is there a responsibility in choosing one option over another? For example: Is there a valid argument for whole-scale slaughter over less destructive methods of solving disagreements? Or let’s put responsibility aside for a moment. Perhaps there is no such thing as choice at all: that the only options available are conditioned, knee-jerk responses. Recently, I read about two teenagers having an argument after school in Richmond, Virginia. The girl turned away and the other party shot her in the back. She was the 100th person to die from gun-related violence in this small, American city last year. In this particular case, I wonder: Were these people even remotely aware of the choices available to them? We read about it all the time: Someone driving a car gets angry with another driver at a traffic intersection. Emotions flare and out comes a gun. Add another statistic to the eleven thousand people who die each year from gun-related crime in America. As I see it, the ability to choose — and choose responsibly — doesn’t exist as long as we remain asleep, unconscious, unaware; at the mercy of our mind and emotions. Could it be we are forever-destined to settle our disputes like animals? Just like primitive man throwing rocks at one other. Are not atom bombs anything more than sophisticated rocks? Rocks or bombs — are they not the same to the fragile flower of human life?

“The man of the future has to be cosmopolitan. He cannot be an Italian, a German, an Indian, an African. No, he can only be a human being.”

Osho, From Bondage to Freedom, Chapter 22

I am not so naive as to suggest that all humanity needs is Osho Dynamic Meditation. I know the world we live in is a complex place. But are solutions really so complex? What is so complex about love? What is so complex about creativity? What is so complex about vipassana meditation? Are the stages of the Nataraj Dance Meditation really so difficult to grasp? At the risk of over-simplifying, I have to ask another question: Have we as humanity really explored meditation as an option? Have we given it a chance? I will be the first to admit, getting out of bed for Dynamic Meditation is never an easy thing at 6AM. But all joking aside, I do feel each one of us ultimately has a choice: either to be creative with our energies or destructive.

“In spite of the third-rate politicians, America is going to evolve, evolve into the New Man, evolve into a new humanity. I have chosen to be here. I have called you to be here.” Osho, From Bondage to Freedom, Chapter 22

The mayor of Hiroshima has written a beautiful letter in the aftermath of 9/11. It hangs in one of the exhibition halls at Peace Park. It is addressed to President Bush, urging him to exercise restraint in his reactions. While offering sincere condolences to the American people, it invites the President and all the world’s leaders to visit Peace Park, to witness for themselves the horror and senseless tragedy of armed conflict. Hopefully, they will gain some insight into humanity’s seemingly endless cycle of violence, thus better understanding the devastating effects of war on the lives of ordinary human beings everywhere. The eloquent mayor offers no ready answers. He just extends an open palm to the world as if to say, “Let us use intelligence to seek more positive and creative solutions to settle our differences.” I was dismayed to learn how few world leaders have visited Peace Park.

“America is certainly the place where the new man is going to be born.”

Osho, The Last Testament, Volume 2, Chapter 28

Meanwhile, we Americans to sip our cafe lattes and drive our Hummers, while our chopper pilots shoot up schoolyards full of Afghani kids playing marbles. I just read how America is now asking hospitals in Iraq to stop keeping count of civilian casualties from Iraq. Amazing how the lives of innocent civilians are referred to as collateral damage (not Americans, of course) such as when one of our precision-guided bombs missed their mark as happened recently, killing over four hundred women and children hiding in a Baghdad bombshelter. Collateral damage we call it. Such a strange choice of words to describe a human life. I guess it’s an easy word for politicians and military brass when it isn’t their kids in the bunker. Now Donald Rumsfield is floating the idea America should begin development of smaller, less powerful nuclear weapons, ones that can be used on the battlefield, ones that don’t kill so many people at once like the Hiroshima/Nagasaki version. Brilliant idea. So instead of weapons of mass destruction we’ll have weapons of controlled destruction. How tidy and efficient. Sanitized warfare. And these are the people setting the agenda for a whole nation? A nation that is supposed to be leading the world by its example? I find this insulting to humanity.

“This is only the American government. Don’t make it equal to America. The people of America are the most innocent, fresh, young — and are capable of giving birth to the New Man.” Osho, Transmission of the Lamp, Chapter 25

In America, we live under an illusion, spun very cleverly by the status quo, of individual freedom, peace and prosperity while a disturbing policy of military adventurism is pursued behind the facade of making the world a safer place. Well, it seems we certainly aren’t making it any safer for the average Iraqi citizen. Why are we looking in someone else’s backyard for weapons of mass destruction when the reality is America is the world’s primary manufacturer of destructive weapons? Mass or otherwise — we make them,

we sell them, we use them at our whim. It’s our business. BIG business. Osho’s observation after living four years in the United States was incisive: “Violence is the religion of America”. My point is: In the current world climate has there ever been a better time to learn the art of celebration? Has there ever been a better time to meditate and to pull the plug on all the bullshit and wake up? “I know. The question is from Milarepa. I can understand your anger. Every sannyasin would like to say ‘To hell with America’! But just say, ‘To hell with the American government!’

“America is far bigger, far more important – and I still hope that the new man will be born in America. These governments come and go; the people remain. The people are the very soul. A country is not made of land, it is made of the people. I can understand your anger, but remember: always to be careful to draw fine lines so that only the criminal is hit, not the simple, poor, innocent people.”

Osho, Beyond Psychology, Chapter 33

As big as the United States is, with all its tremendous resources and potential, I guess I expect a little more from the country of my birth. After all, it does happen to be the place Osho indicated the New Man will appear. The unfortunate reality as I see it: meditation has yet to take root in America. I’m not saying that unless you are into Osho you can’t know meditation. But for a man who is universally regarded as one of the world’s greatest mystics and religious thinkers of all time, I find it bordering on conspiratorial his books are not more-readily available in mainstream bookstores across the country. You’ll have no problem finding titles reflecting the latest trends from Buddhism, yoga, Dr. Phil.. Perhaps it takes a Madonna or a Sting to start doing Kundalini; or Oprah reading “Way of the White Cloud” to turn our heads. But let’s face it: In America, it’s easier to be entertained than to meditate. Why? Because meditation is sure to change you. It is sure to shake your tree. Meditation doesn’t screw around. It works. It disturbs. Yes, it creates waves in our safe, comfortable little lives, there’s no way around that. And yes, there is every possibility if we start meditating we might come to see some not-so-pretty things about ourselves along the way; a possibility when we start peeling the layers of the collective onion, we’ll come across a little bit of Saddam or Bush hiding inside all of us. Let’s be honest: For most of us, I think that’s a very scary prospect. But then again, coming back to that word ‘choice’. We have to want to wake up. Meditation takes courage and commitment, to stand up, alone if need be, and say: No more Hiroshimas. No more Nagasakis.

“What happened in America with me is nothing new. It has always been happening. You have to understand one thing, that whenever there is somebody who has a message for you which goes against your traditional ways, your orthodoxy, your conditioning – then your whole priesthood, your politicians, the status quo, all the vested interests are against such a man. For the simple reason: because he is a disturbance. If people listen to him there is going to be a revolution.”

Osho, The Last Testament, Volume 5, Chapter 23

Walking away from Peace Park, I felt a new clarity arising in me. I remembered all the times I heard Osho speak about the vested interests, politicians, priests, and the masses who worship their every word; how lies are continuously fed societies in an effort to manipulate and control them. I don’t think what’s happening now with George Bush is anything new. But for myself, I see my choices more clearly now. I get reminded of these choices every year at the events, seeing people from all different nationalities and backgrounds coming together to meditate, celebrate, dance, sing, to love and rejoice in their life-energy. They are just ordinary people like myself, making positive choice, for themselves and on behalf of humanity; choices that are in the interest of life, creativity, love, joy — not death, misery, and destruction. The responsible choice as I see for myself – and my answer to Hiroshima’s everywhere – is to wake up. Places like Peace Park remind the distance we still need to travel before claiming ourselves civilized. And for God’s sake, let us not forget our sense of humor.

Chakraman

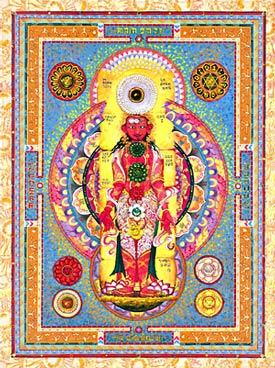

As a theme for this year’s tours, I have chosen a symbolic figure from the caves of ancient India called chakraman. In our present time, chakraman exists as a beautiful painting by my friend and fellow sannyasin, mandala-painter Paul Heussenstaam, also known as Vibodha. You can learn more about him and his work at www.mandalas.com. In his own words: “Chakraman literally glows with the capacity to heal and teach using the ancient chakra energy-medicine.”

In my understanding, this energy-medicine is another name for meditation. Osho has spoken on various occasions about the chakras and their significance to the seeker, explaining how the system of the chakras is like a map, invented by the Buddhas, to help us better understand the stages of the spiritual search – just as the Zen people use The Ten Bulls allegory.

Osho describes the chakras as being metaphoric wheels – not centers – of energy in our psychic body. Speaking on them from many perspectives – I found over two hundred references to the word ‘chakras’ when I ran a search – his essential point is: When all the chakras are open, relaxed, natural – our energy circulating freely in each one – celebration overflows, creating a tremendous potential for healing.

At this year’s events, we will be experimenting with many different meditations to open the various chakras – removing blocks, releasing repressed, locked-up energy – thereby making us available to higher dimensions of consciousness. Chakraman is shamanic, a channel for the mysteries of existence. It is a powerful symbol for the healing power of meditation. I am grateful to Vibodha for his support in this project.

In the months ahead, I look forward to coming together with seekers throughout the world, to share a fresh new vision of meditation and celebration – and the music! In addition to Japan, Europe and America, I am excited to visit some new places like Mexico for the Spirit Festival – and possibly Brazil and Taiwan. So stay tuned and watch the schedule for developments. It’s going to be a great year!

Year of the Monkey

According to the Chinese calendar, this is the year of the monkey. I did a little bit of research and came up with: Monkey years hold bright prospects of a fascinating future, rich in the unexpected. They are years of transformation.

One thing I am noticing about the New Year so far: It’s moving fast! This month is a busy time for me: scheduling, arranging the many details of the tours. It is also a time for letting go – being grateful for the amazing year that was and welcoming the year that will be. Always at this stage, the tours look like a big puzzle – all the pieces scattered out before me, impossible to see the overall picture, how in the world it is ever going to fit together. But, as those of you know who have ever done a puzzle, peaking at the picture on the box-cover spoils the fun. The real joy is in watching, as piece by piece, the unknowable unfolds and the picture takes shape. I know all too well, it won’t be long before I’ll be shaking my head marveling how everything came together so, as it does every time. Amazing – this will be the tenth year for the tours!

Monkeys are bright, playful creatures: intelligent, creative, humorous. I thought it a fun way to start the New Year by sharing some ‘unreleased’ photos from my last trip to Japan. One of my dear friends lives there, Vimal. He’s the guy who used to write the jokes for Osho and sometimes ask the discourse questions when Maneesha was having a migraine. He is one of those rare people I can always have a belly-laugh with. Don’t ask me why. Maybe it will be clearer when you see the pictures. Just a couple of monkey’s having a ball at your local karaoke bar.

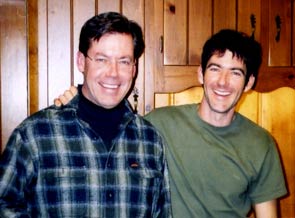

My mom turned 77 this month. And Jim, my youngest brother many of you know from the tours last year, also had his birthday. So my family and friends gave them a wonderful celebration.

The year of the monkey is already shaping up to be a fun one – with many more laughs and surprises ahead. So what are we waiting for? Let’s enjoy!

|

|

| Christmas Brunch – Mom and Pravasi at the River’d Inn, Virginia | Birthday Party – brothers Paul (r) and Jim (l) |

|

|

|

| guitar solo – Hotel California | legendary riffs | oops … bum note |

|

| Mukti, Vimal, and Noa-chan |