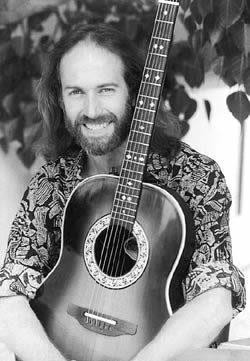

Director of the Osho Institute of Music and Celebration

Osho Times International – Volume 4, Issue 2, January 16, 1991

Conducted by Swami Anand Subhuti

OTI: Milarepa, can you tell us about your relationship with Osho?

Milarepa: Although I had speaking darshans with Osho in the early days of sannyas, my relationship with him has never been a personal one. It was and still is an inner one, something deeply connected with the mysterious world of meditation. However, as I moved deeper into meditation, so did my relationship with Osho change and become more intimate.

OTI: Can you explain?

Milarepa: When I took sannyas in 1976, Osho was living in Pune, India. During these early years, I came and went from the ashram many times. When I was there I meditated, did groups, attended discourse, and finally at some point jumped into work. Osho seemed like god to me then representing something unreachable, unattainable. Most of the time in those days, I felt like I was standing in a deep valley looking at a far away Himalayan peak. I can see now this was more my own projection for my understanding since is: The master is only as far away as you are from yourself.

In the beginning, my mind and its strategies to avoid meditation were very strong. I spent a lot of time and energy circling around the periphery of the Commune, Osho, and myself. In spite of this, I knew without a doubt I had found what I had been searching for my whole life, perhaps lifetimes. I was groping in the dark, but I had seen a glimpse, a light, a possibility. By the end of Pune One (1980), I was working full-time in the Commune. And my disciplehood began to unfold and flower.

OTI: Osho has a fondness for you. When did this start becoming obvious?

Milarepa: In 1980, Osho left India for America. I, like many other sannyasins, moved to Oregon where work had begun on the ‘new commune’. Osho named it Rajneeshpuram. We knew it affectionately as The Ranch. This was a big shift for many people, a huge change in the atmosphere from our idyllic life in India as orange-robed meditators, where everything and everyone seemed so ‘spiritual’. I have a friend who still believes if Osho had never left India, we would all have been enlightened by now. I won’t comment on this. But I will say that cowboy hats and boots replaced our flowing robes and spiritual good looks. At least for the time being! In that central-Oregon desert where thousands would eventually come, work became our meditation. And I mean work with a capital W! Twelve-hour days were considered the minimum.

I had been at the Ranch about a year when we opened a nightclub in Portland, Oregon called Zorba the Buddha, where I played in a band every week for one-and-a-half years. One evening, just as I was finishing a sound-check, Garimo, one of the Ranch coordinators approached me and said, ” Milarepa, have you got a minute to sit down?”

I thought something terrible had happened or I had screwed up something.

“Your Master was talking about you last night,” Garimo said.

I was incredulous!

She continued: “Osho was speaking to some of us from Jesus Grove about relationship issues (it seemed many of the couples working around Sheela had been having a rocky time – including Sheela herself!). Osho used you and Shunyo (my girlfriend at the time) as an example of how he envisioned men and women should relate. He shared a story he had often told in discourse of a man and woman who lived at opposite ends of a lake. They were deeply in love but only met by chance when sometimes out rowing on the water. He said it was beautiful how Shunyo and I met like this couple. When we had the feeling to be together, we would meet and enjoy. And when we were apart, we were also happy and content in our aloneness.”

Although I had been a sannyasin for six years, this was the first time I was aware Osho knew who I was, much less knew my name. There is a Zen story about a young man who comes to the master to be initiated into meditation. For seven years, he meditates and the master never so much as looks at him, as if the man doesn’t exist. Then one day the master walks by and looks at him. This look from the master stirs something deep inside the man, inspiring him to go deeper into meditation. Another seven years pass. One day the master catches the eye of the man and smiles setting the disciple’s heart on fire. Seven more years pass. Then one day the master walks by and utters the man’s name. The sound of his name on the master’s lips floods the man’s heart with ecstasy. Another seven years pass. One day the master, who has become old by now, walks by, touches his head, and the disciple experiences a silence not-of-this-world. Something of the beyond is transmitted through master’s touch. Tears flowing, he touches the feet of the master and the master says: “Your tears show me you have understood all there is to know. There is no need to continue being here. Go and live in the world as a madman, singing and playing on your instruments.” I love this story.

OTI: And did Osho mention you again?

Milarepa: About a year passed since my chat with Garimo. One day as I was finishing lunch, Nivedano, Osho’s beloved drummer, walked up and said: “Hey man! Did you hear? Last night your master was talking about you again!” (Osho had been speaking to a small group of people every night at his house for the past few months). I could see Nivedano was thrilled. IWhenever someone in the Commune got a little extra nod from Osho, it would spread to every heart like wildfire and everyone would enjoy by association. Such was the intimacy of the Commune. At first, I thought Nivedano was just teasing, but my heart told me otherwise. I knew something amazing in the life of a disciple was happening, again. The master had smiled at me.

Later that same evening, Shunyo, who had been present in the discourse, told me of how Osho had been joking about me having a big reputation with women, calling me a ‘Lord Byron type’. He said he was puzzled, though, because whenever he stopped his car in front of me “He could see the drum, but not the drummer.” I had been playing a drum at Osho’s drive-by – a highly celebrative daily event that happened each day after lunch where the entire Commune would line the road to greet him on his drive with wild singing and dancing.

OTI: How did you feel upon hearing what Osho had said?

Milarepa: Nothing short of ecstatic: like being loved deeper than I had ever been before; like being seen to the core by someone and showered completely with love. Soaking you! I have never felt the word ‘yes’ so deeply in my entire life.

OTI: Anything more from the Ranch times?

Milarepa: A few nights after this episode, Osho reported at the end of discourse he had heard a rumor I was going to England. When asked by someone what he thought he said, “All I can say is God save the Queen.” Osho certainly loved to tease me. But I always felt it came alongside a deeper meaning, as if he wanted to convey something immensely valuable to me.

OTI: In 1985, Osho left America and went to India, Nepal, and then on a World Tour. You caught up with him in Uruguay?

Milarepa: Yes. After the Ranch dissolved, I went to live and work in Los Angeles. Shunyo left the Ranch with Osho as part of His team of caretakers, so we were separated for some months during this time. In our six years together, although we were not always lovers we maintained a close friendship. I think we shared a mutual understanding that, in spite of the love we had for each other, ultimately we were sannyasins, fellow travelers, bound in spirit by a deeper love: Our love for the master.

One day in Los Angeles, I received an unexpected phone call from Dhyan Yogi, the person responsible for looking after the many practical things connected with Osho’s World Tour. He invited me to come to Uruguay where Osho was staying at the time. Often people ask me about these times in Uruguay, what it was like to be there. Have you ever read ‘Mojud: The Man with the Inexplicable Life’? This story is a good description of how I felt being there. In other words, incredible!

When I arrived, Osho had just started giving discourse twice a day in a small room in the house where he was staying. There were about twenty of us present. This was every sannyasin’s dream, such intimacy with the master. The whole situation was to say the least very inexplicable.

OTI: Did your disciple relationship with Osho continue in Uruguay?

Milarepa: You could say that! In Los Angeles, I had shaved my beard and dyed my hair black just for a change, to have some fun. When Shunyo and Avesh (Osho’s chauffeur) came to meet me at the airport, they drove straight past several times not recognizing me. That same evening in discourse, I was sitting in the back of the room, which was still closer than I’d ever been to Osho. I was totally absorbed in meditation when suddenly it was as if someone was shining a spotlight on me. I was wide-awake inside, red-alert. I started paying attention and tuning into what Osho was saying. He was talking about how ridiculous men look without a beard. And wouldn’t it be strange if your girlfriend decided to grow a moustache? Then reality dawned. Oh my god, he was onto me! Then he says something like: “Just look at Milarepa, sitting there in the back looking like a complete idiot. He has shaved his beard and lost all his grandeur.” It was Osho’s way of saying hello. By the way, I grew my beard back really fast.

OTI: Listening to the Uruguay discourses, it seems like you asked Osho many questions. Is that right?

Milarepa: I had never asked a discourse question until Uruguay. I had always assumed, I think like many others, I had no questions to ask. It felt more than enough just to be in the his presence. One day during a morning discourse, Maneesha ran out of questions. It was a light, but awkward moment. Osho sat for a minute, then smiled and said unless we had questions for him, there was no reason to speak. He said for us to take it as a game, to write questions even if they didn’t feel like our own, because someday someone might benefit from our asking. And to remember that our questions were creating the opportunity for him to be with us and to share his being. And that although the real transmission happens in silence, we still need the discourses to create a context for this.

So, this is how I started asking questions. Every morning after discourse, I would take an hour to be alone and write. Very soon I realized what a unique opportunity it was to everyday expose myself and get Osho’s immediate feedback. Sometimes he would accept my questions, sometimes he would reject them. As the days went by, I began to feel him steering me deeper into uncharted waters of myself by the ones he chose, and equally important by the ones he rejected. Each new morning, as I would prepare fresh questions, I would say to myself, “OK, he chose this one yesterday and rejected that one. Hmm … so perhaps this is the direction I should take.” As the days went by, I felt he was leading me into the unknown, introducing me to new dimensions, previously unexplored areas, of my being, taking me always deeper and deeper into myself.

OTI: He liked to answer questions from you that were humorous, right?

Milarepa: Towards the end of our stay in Uruguay, Osho had started choosing questions of mine that had a humorous potential, ones he could use to make everyone – including himself! – laugh. In the first few weeks after I arrived, the tone of his discourses was quite serious: a lot of politics and talk about the world situation and so on. It provoked my mischievous side, so I would try to provoke him as well – and that divine smile of his – with my questions. Seeing him laugh would just melt my heart. I would ask him things like “Beloved Master, are you just pulling my big toe?” and he would laugh and then proceed to give the most amazing answer, one that always seemed to perfectly suit the occasion. And at the same time find its mark in me! Many times I felt I was on the razor’s edge. I never quite knew which way the wind was going to blow when I asked a question. Sometimes I experienced him like a lion, playing with me, a small mouse. In the last few Uruguayan discourses, Osho was mostly saving my questions for the end. It was as if he wanted to end the discourse on a special note, leaving us all in an ambience of his choosing. I would invariably watch him disappear around the corner, chuckling to himself, leaving in his wake a room overflowing with laughter, love, and the fragrance of the divine.

OTI: Were you playing music in Uruguay?

Milarepa: Yes. Towards the end of our stay, Nivedano and I would play for the discourses as Osho entered the room and left. It added the dimension of celebration. Dancing with him, singing our hearts out, made everything seem complete and total.

OTI: Was it on the World Tour that Osho gave you the Institute of Music and Celebration and made you its director?

Milarepa: This happened after Uruguay when Osho was staying in Portugal. It was right before he returned to India and concluded his World Tour. We were all staying in a big house surrounded by a beautiful pine forest. It was a very secluded and silent place, so much so that you could hear pinecones bursting open in the heat. The governments of the world were really after him at this point, trying to limit his movements, trying to prevent him from settling anywhere, trying to keep him from being with his people. It is an understatement to say he was being harassed.

Shunyo and I were staying in the room right under Osho’s. One night as we were going to bed, about eleven o’clock, Amrito (Osho’s personal physician) knocked on our door. “Milarepa, I have a message for you from your master,” he said. “I was on my way out of Osho’s room, and as he was pulling up the blankets over his head to go to sleep, he seemed to suddenly remember something: ‘Oh, and give Milarepa the Osho Institute of Music and Celebration. And make him its director.’ ”

OTI: After Portugal did you return with Osho to India?

Milarepa: Not at first. I went to London with Shunyo. We stayed together there about a week, then she left for India and I followed on a week or so later.

OTI: And this was the end of the World Tour, right?

Milarepa: Yes, that’s right. Osho returned to India and stayed in Bombay for about three months. It was a transitional time. But Osho, never one to miss a beat, resumed the discourses a few days after arriving back in India. In his own country, he suddenly seemed safe from the international, political attempts to harass him. I think there was a collective sigh of relief from sannyasins all over the world because his people could finally be with him again. I must say, it felt great to be back in India. It was so much more relaxed than the West had been. I wrote one of my favorite songs during this time: Osho, We Your People. The words came to me while I was walking along Juhu Beach one evening – a balmy night under the stars, listening to the soft surf of the Arabian Sea. I hadn’t felt so happy and content in a long time.

OTI: And did this cat and mouse game with Osho continue in India?

Milarepa: Yes. In fact, more and more. When Osho left Uruguay, because it all happened very suddenly, there were a handful of pending discourse questions on Maneesha’s clipboard, and a few of them were mine. She planned to keep them safe for the future when, and if, the discourses ever resumed. A few months later, I was in England waiting for a flight to India, when I received a message from Shunyo (already in Bombay at this point) that Osho had answered one of my questions during the previous night’s discourse. On hearing this, I experienced a love that knows no boundaries, no time. I was in England, Osho was in India – both of us separated by oceans and continents – yet I understood time and distance made no difference in my connection with him. Days later, I arrived in Bombay and was soon at it again, writing fresh questions, and trying to provoke that divine smile. Touché!

OTI: And then Osho returned to Pune. This seems to be the time the music really took off – both for you and the Commune.

Milarepa: Pune Two as it is called was a peak in this sense. Osho resumed the discourses a few days after returning to the ashram and I had a strong feeling there should be music for them. I had already seen in Uruguay how well it complemented the meetings, providing a joyous backdrop to the things he was speaking about. So I asked through his secretary what he would like to have happen and he sent the message that yes, he wanted music for the discourses, Indian in the morning and Western in the evening, and that I should coordinate both. And so began the Osho Institute of Music and Celebration.

Everything expanded quickly as the months went by. People began arriving by droves from all corners of the world. We started recording music from the discourses and making tapes to sell in the Commune’s bookshop. We also organized many creative things for Buddha Hall like variety shows, music groups, dance and art performances.

OTI: Yes, those tapes you mention are loved and listened to by many people. Do you have a favorite?

Milarepa: No. I love them all. Each one represents to me a certain phase of the music. For instance, the music from Yes To The Riverhappened during the period when Osho moved the discourses from Chuang Tzu Auditorium to the newly-constructed Buddha Hall. Although the album features recordings from both venues, the overall feeling reflects a freshness, an innocence, that was prevalent in the Commune at this time. I think it comes across in the music. It’s something very tangible. Each of these albums is like a mirror, reflecting specific spiritual dimensions in time: of the Commune, life with Osho, the atmosphere of the discourses, and most importantly: my own process.

OTI: And how was it playing music in Osho’s presence?

Milarepa: Well, if you are a musician, in my opinion there is no greater experience than to play for one’s master. It is the highest calling. Expressing one’s creativity in the service of meditation, you help create a special space where hearts can open and people can receive the many blessings. For a musician, a creator, this is ultimately fulfilling.

OTI: Did Osho ever comment on the music?

Milarepa: Very rarely. I have always felt Osho’s one hundred percent trust in me regarding the music. His silence and love say more than any words. Osho knows my heart. And he knows the hearts of everyone of his musicians, of each of his people in fact. He knows our love arises from very deep feelings of gratitude. He knows we only want to do our best, to give our best to him, all that we are capable of, as this is ourjoy.

OTI: And did your playfulness with Osho continue through your questions during this time in Pune Two?

Milarepa: I like to think I have matured since those intimate times in Uruguay. So when Pune Two came along, I sometimes thought I had some real questions to ask. Serious questions! (laughing) And yes, to answer your question. There was still a lot of playfulness, laughter and humor. From both sides. Osho would do mischievous things like sign my name to someone else’s question. Or take my question and sign it with someone else’s name! Sometimes he would laugh just hearing my name read. At other times, he would appear stern and administer a ‘hit’. I could never predict what he was going to do, nor how he would react. Want some advice? Never try to second-guess the master.

OTI: And the Commune continued to flourish during this time?

Milarepa: Yes. By late 1989, the Commune was flowering again in all dimensions. Like a rainbow. The ecstasy of celebration was rising higher everyday as, in retrospect, the master was preparing to leave his body. The intensity in fact was often overwhelming. I remember sometimes feeling inadequate with just my guitar and songs to offer and expressed this in a question Osho answered on Enlightenment Day, March 21, 1987. He seemed surprised and responded that the offerings of the heart are more valuable than any mundane thing the world has to offer

and that I should understand this.

.

OTI: How do you experience different phases in Osho’s Work?

Milarepa: Life with Osho to me is like a river: always moving, always changing course, always unpredictable. As I see it, Pune One was a catharsis phase: a cleansing of our collective unconscious, helped along by the groups and therapies. It was as if Osho was creating a foundation to what would follow. Work came more and more into focus as the Commune, the sangha, grew and flowered.

This phase reached a peak at Rajneeshpuram. When the Ranch finished, there was a big dispersion of energy like a ripe seedpod bursting. The Commune dissolved and his people moved back into the world while he moved from country to country harassed by every government. But Osho had a knack for transforming negative situations and making something beautiful out of them. Hence, many positive things came out the phase he called his World Tour. Ultimately, this phase manifested with him returning to India, where the Commune again flourished reaching yet another peak, the one we know as Pune Two.

Although work was, and still is, considered an important part of Osho’s vision, in the last years of his life, he began to emphasize creativity as a way of expressing and sharing the fruits of our meditation. His discourses took on more and more the flavor of Zen and it was clear he wanted each of us to become our own individual, not dependent on anybody else. Including him! Nor dependent on anything, even the Commune.

Taking care of the music around Osho for me has been about allowing things to expand and flow with him, so that the music reflects as clearly as possible his vision and the things we are continually learning by being with him. In this way, music has became my meditation.